Second World War in York

People gathered around the wireless on 3rd September 1939 to hear Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain announce that Adolf Hitler had not withdrawn his troops from Poland and so he declared that ‘this country is at war with Germany’.

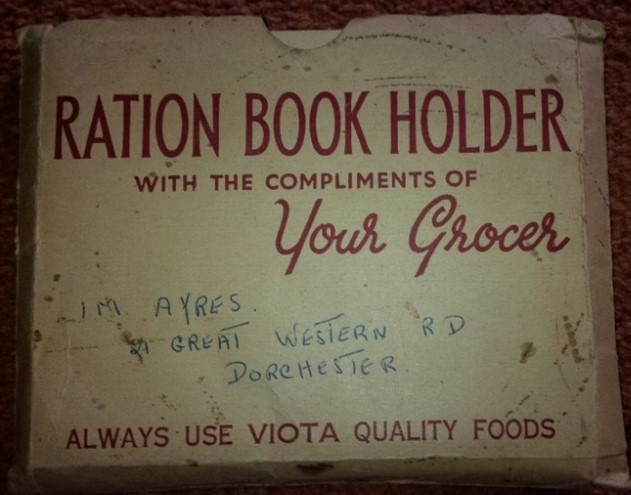

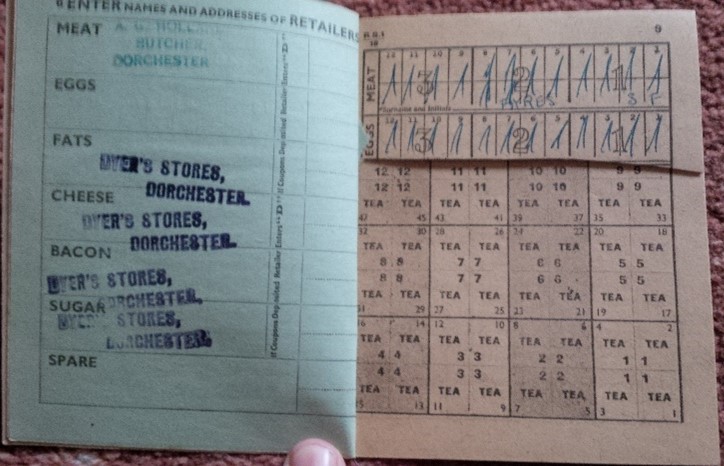

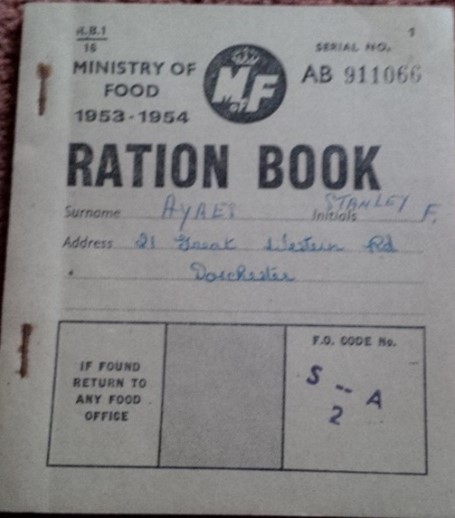

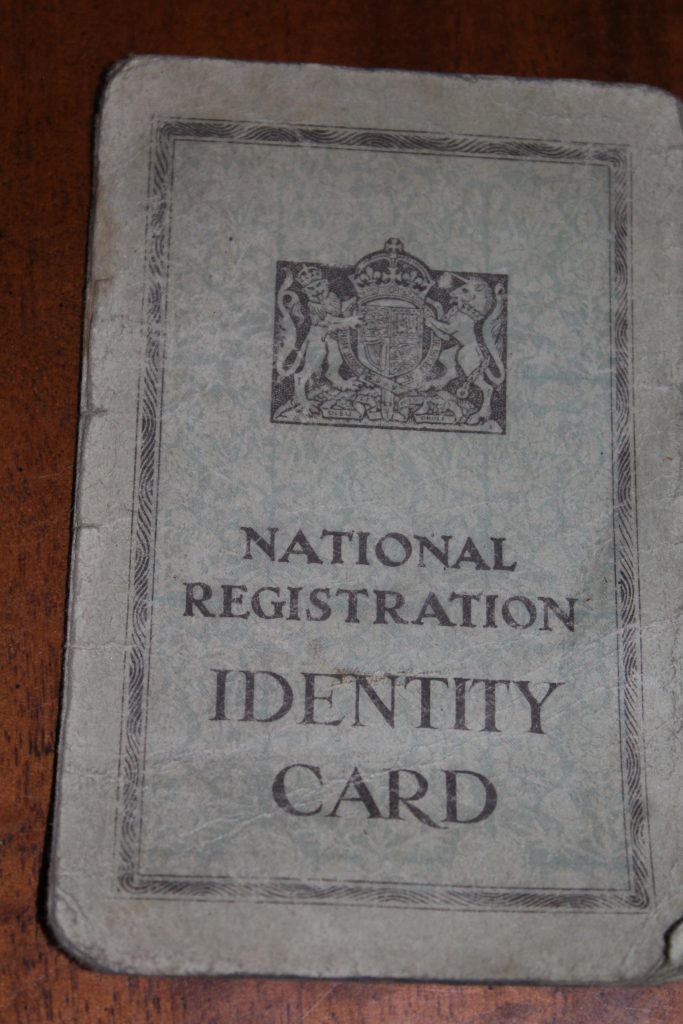

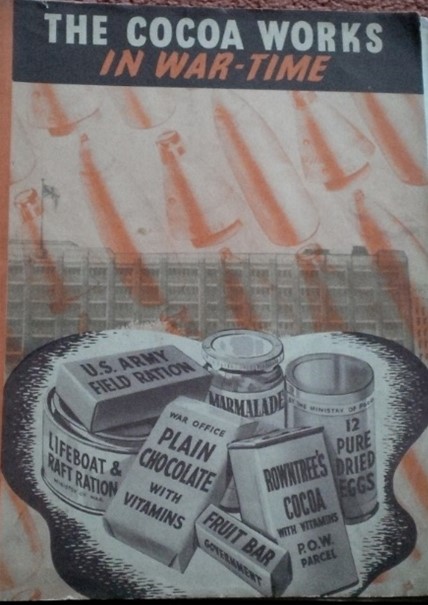

The first British warship to be sunk by a German torpedo was HMS Courageous on 20th September 1939. It had been patrolling shipping lanes off Ireland. One of the dominating factors throughout the war, later described by Winston Churchill, was getting enough food and goods through the submarine blockades. Before the war, one third of Britain’s eggs were imported. Although we produced enough milk, most animal feed was imported. Good nutrition was vital for everyone. It was clear that a system of rationing would be needed. A country-wide register was taken in 1939, which was used to issue ration books, and identity cards. Rationing didn’t finish until 1954. Canteens were set up in factories and on docks and people working on farms and down coal mines were given extra rations of cheese. Working people in York could go to government-run British Restaurants for a hot meal. The one in the centre of town was situated down Aldwark.

Operation Pied Piper led to the evacuation of millions of people, mainly children, from built-up areas of Britain to the countryside as well as overseas including Canada and New Zealand.

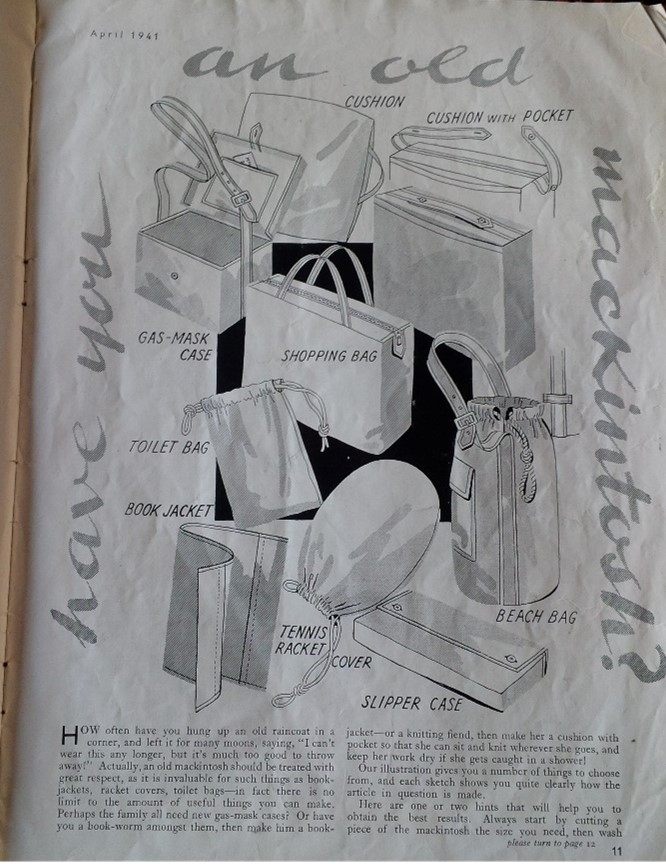

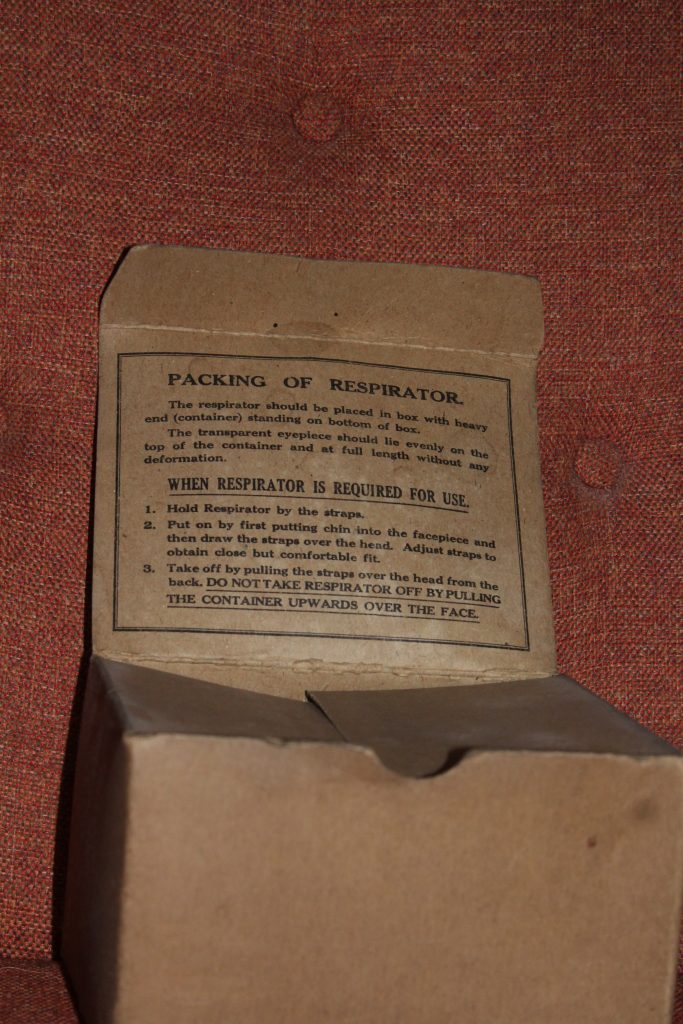

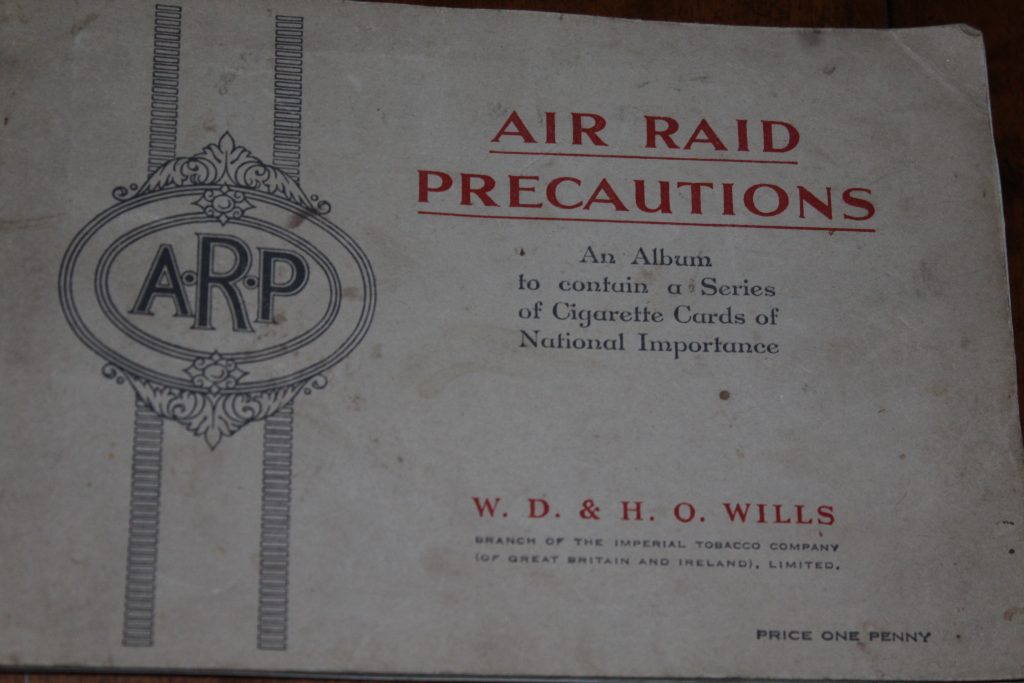

Due to a worry that gas might be used during air raids, gas masks were distributed from stores at the Tramways Depot in Fulford. Rowntree and Co and Sessions Printers had made boxes for them. Residents were given a copy of ‘A Guide to Householders’. Information and maps of air raid shelters were published in the local papers. The Ministry of Home Security leaflet issued in September 1940 said: “Everyone who has no form of shelter should busy himself at once with selecting and preparing a refuge room.”

What did York firms do to help with the war effort?

Rowntree’s continued to make some chocolate, but this was mainly for troops and Prisoners of War. They made jams and marmalades for Frank Cooper of Oxford. The cream department made Ryvita, national milk cocoa, dried eggs, household milk and munitions. In June 1940, the department which used to make fancy chocolate boxes was taken over by the Royal Army Service Corps, Northern Command and became known as Number 14 Army Supply Depot. Three hundred clerks from the Royal Army Pay Corps moved into the new office block. In 1941 a section of the gum department was converted into a secret fuse factory, named County Industries Limited. It was managed by Neville Sparkes from the gum department. The powder they used turned their skin yellow. It came from the Royal Ordnance factories in Chorley and the fuses came by boat from Doncaster. The sawmill made fuse packing cases.

Messrs. Cooke, Troughton & Simms, the precision instrument makers, had moved to new premises outside York in 1939. The factory was called ‘Kingsway North’ to try to disguise its true whereabouts from enemy spies. It was painted with camouflage paint by late 1942. In 1941, part of the almond block extension at Rowntree’s was taken over by Cooke’s, who made military telescopes and tank periscopes there. This part of the business was called ‘Hambleton’ and employed 300 people.

F Hills & Sons, from Manchester, moved into Terry’s factory to make Jablo propeller blades for planes. Noel Terry became Controller of No 9 Group, Royal Observer Corps. Chivers and Sons the jam makers moved into Terry’s and stayed until 1954.

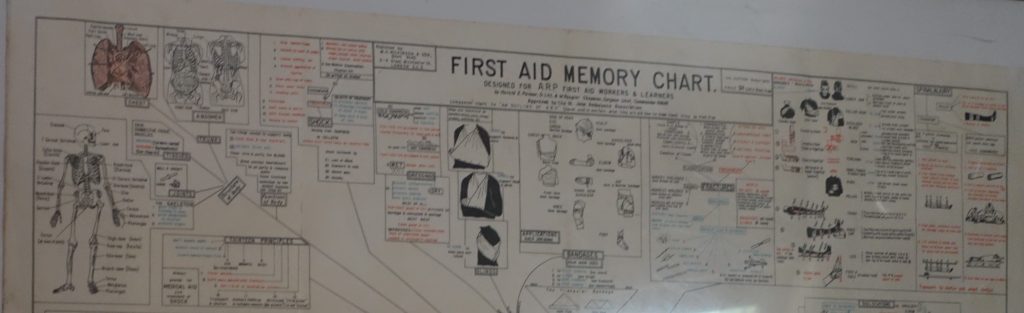

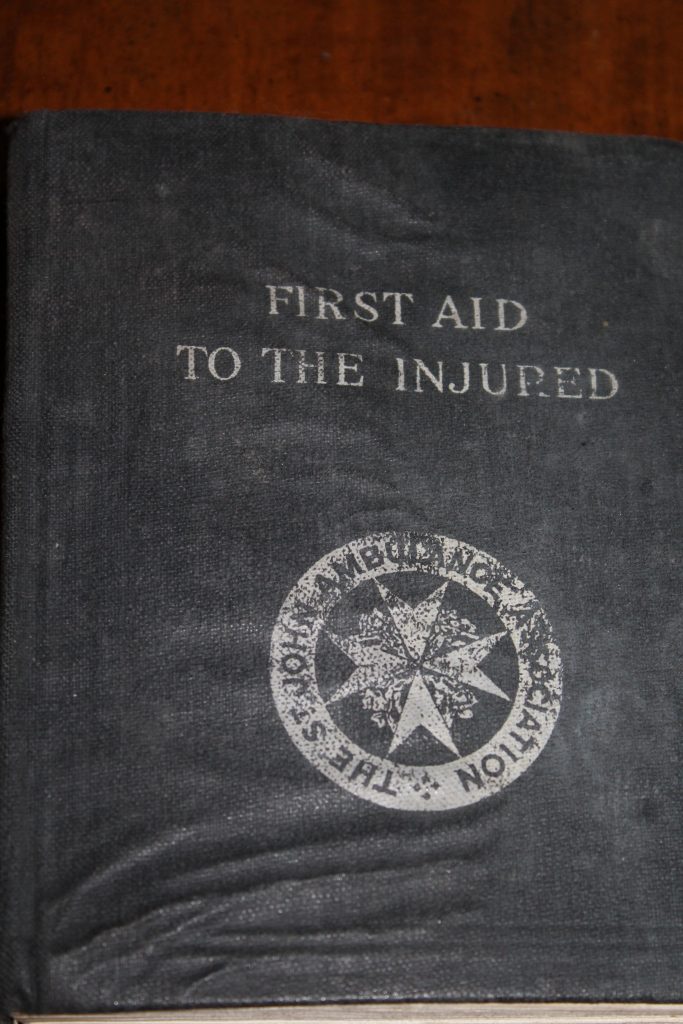

Workers were given a war bonus: £10 for men and £6 for women. In addition to working, many adults also volunteered for civil defence. So, what roles could people volunteer for? These included air raid precaution wardens and first aid parties, Women’s Voluntary Service, British Red Cross, Royal Observer Corps, ambulance attendants, rescue parties, auxiliary fire service, nurses, special constables and fire watchers. Warden posts were at places like the basement of the Grand picture house, the isolation hospital on Beckfield Lane, White Cross Lodge near Rowntree’s and Bootham Grange.

The large companies such as Rowntree’s and the railway had their own air raid precaution wardens. Cooke’s and Rowntree’s had their own Home Guard units. Many people involved in this civil defence work had seen service during the First World War.

Air raid wardens had to complete forms which included the type of bomb, position, number of casualties, any damage to services such as sewers or gas supply and where unexploded bombs were located. Fire watching shifts lasted from 10pm until 7am. The air raid warden posts were equipped with stirrup hand pumps. These were helpful for incendiary bombs.

People were living on little sleep, rationed food and had to be mentally healthy. It was tiring, dirty work. Some firewatchers and air raid precaution wardens died during raids, including when the Bar Convent was bombed.

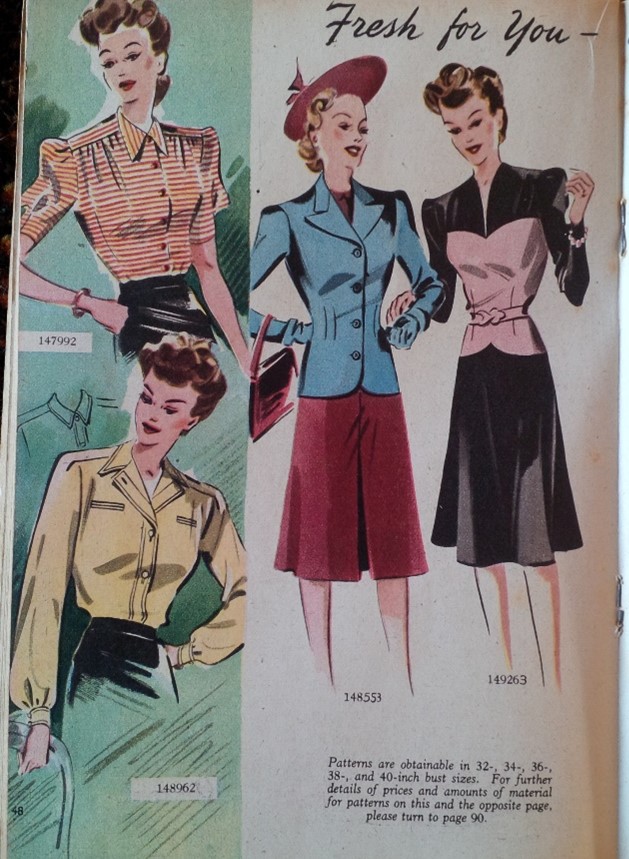

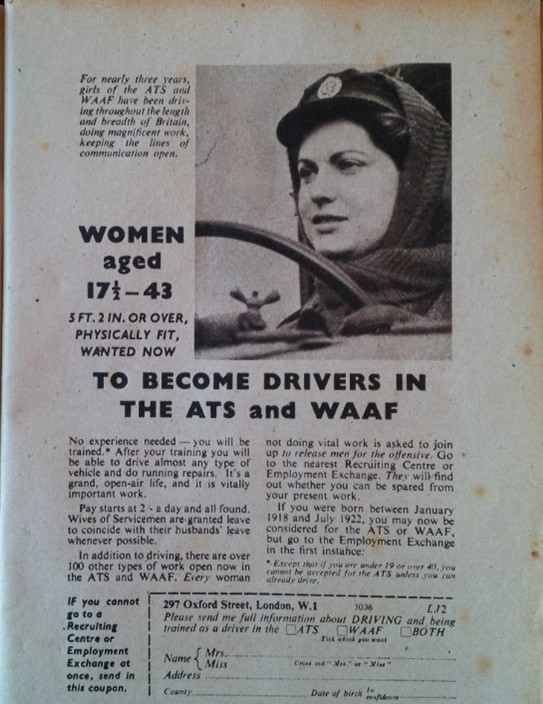

In July 1939 women were asked to help on farms and in forestry by joining the Women’s Land Army. In 1941 young women had to choose between factory work or the auxiliary services, which included the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force and the Auxiliary Territorial Service. By 1943 young women had to choose between factory work or the Land Army. The work was hard and they had to work long hours. Some unmarried women from York were sent to Bradford for war work to make wiring for planes. The women would have to lodge with a family. My great aunt Nell Cooper lodged with Mr and Mrs Binns.

What temporary services were put into place at this time?

34 rest centres, with a control centre in Museum Street were set up. These included St Georges Methodist Chapel on Millfield Lane; Clifton Methodist Church; Heworth Church Institute; and St Aelred’s School. Rowntree’s hall helped with the homeless. A broadcast appeal at Rowntree’s produced many offers of temporary homes for people whose houses had been bombed.

There were two medical rest centres, 21 Nunthorpe and 48 Burton Stone Lane. Hostels were at 59 Huntington Road, 3 Bishopthorpe Road and 6 St Peter’s Grove. Naburn and Fulford Hospitals were used as emergency hospitals, to supplement the City and County Hospitals. Naburn was being used for Prisoners of War by 1947. First aid posts had been set up, for example at St George’s swimming baths, Beckfield Lane and near Hungate Stores. A famous York GP, Dr Dench, was the doctor for the first aid post at Walker’s Horse Repository at Tanner’s Moat, a sort of car park for horses.

A former school on School Lane, Fulford, was used as an ambulance station and first aid centre. St Barnabas’ School centre opened to provide dinners. The casualty information bureau and general information and tracing services operated by the Women’s Voluntary Service were aided by a keen staff of searchers and messengers, most of whom were students from St John’s College on Lord Mayor’s Walk.

To deal with the bodies of people caught up in the air raids, temporary mortuaries were made at the York Race Committee Stables on Tadcaster Road, the former Hunt’s brewery on Aldwark and the cattle market butter shed on Kent Street.

Rescue parties were based at the Foss Islands Depot, Scarcroft and Acomb. The National Fire Service had a river patrol boat. A bomb disposal squad came from Leeds.

So, did York suffer from many air raids?

York saw 11 raids in all. Four raids in 1940 had affected the waterworks and the railway’s power station on Leeman Road. On 2nd January 1941 incendiary bombs caused fires in St Margaret’s Church; Bellerby’s saw mills in Hungate and Lazenby’s Garage on Hull Road. On 16th January 1941 at 3.30am 1kg incendiary bombs caused damage to St Maurice’s Church, Monkgate and the Presbyterian Church on Priory Street. An hour and a half later 8 high explosive bombs fell in The Groves. One fell near the air raid precaution warden’s post at the St Thomas’ Church end of Lowther St. The warden escaped injury. Piggeries and a garage behind 57 Eldon St were damaged.

Starting at 2.30am on Wednesday 29th April 1942, York suffered its worst air raid of the war. This followed German Luftwaffe raids on Norwich and Bath, so-called Baedeker raids, named after the famous travel guide. The Luftwaffe bombarded strategic targets, including railway lines, the station, the Carriage Works and Clifton airfield. The Guildhall and St Martin-Le Grand down Coney Street, were burnt out. Damage was caused to the railway coal depot on Leeman Road, but the engine sheds had a narrow escape.

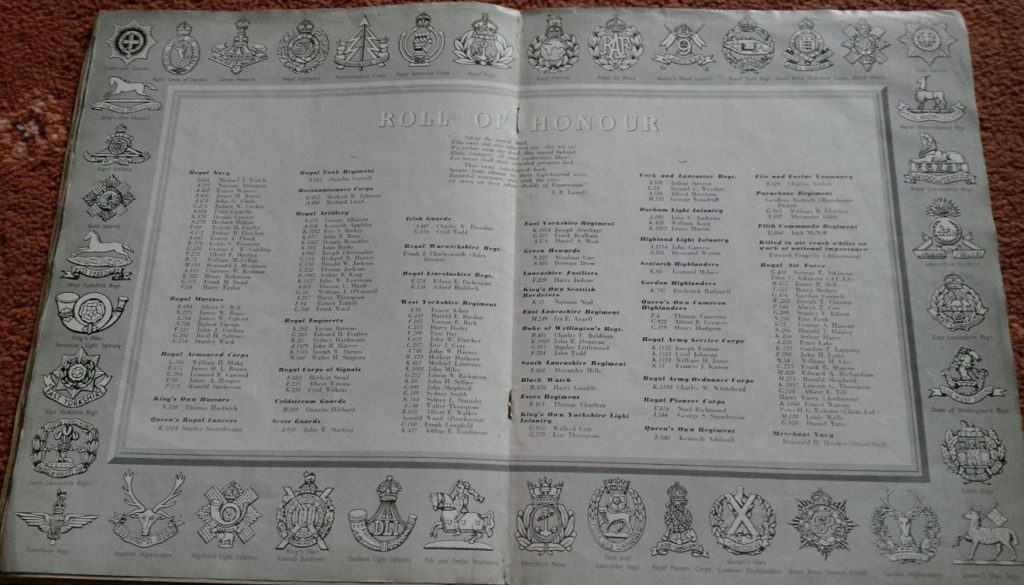

On this day alone, there were 92 casualties. Although official sources gave the number of attacking planes as only about 20, the Royal Observer Corps put the figure as considerably higher. The Daily Mail reported the following day that ‘The gates of York still stand high, like the spirit of its people who, after nearly two hours of intense bombing and machine-gunning, were clearing up today.’

The Dean of York, the Very Reverend Milner White, said in May 1942: “We remember you, our dead. God give you rest and light and joy and life – and York do them honour, who paid our toll with their all”… “That night is over, but it has left us with a proud standard for the days which lie ahead, to which we rededicate ourselves”.

On 2nd August 1942 warden post C3 reported four high explosive bombs. A bomb in Skeldergate caused extensive damage from Micklegate to Burton’s corner on Coney St. Post G3 also reported on damage to Albert St, Hope St and Salisbury St.

On 29th September 1942 an unexploded bomb was found behind Bellerby’s painters in Grape Lane. The premises were badly damaged. There was also damage to Haws Garage, Lowther St. There was an unexploded bomb at Tang Hall Park near the park keeper’s house. Cookes, Troughton and Simms at Haxby Rd reported at 1.50am that there was a suspected unexploded bomb in the factory. On Fifth Avenue there were two unexploded bombs in the Derwent Valley Light Railway embankment and five at Foss Islands Cattle Dock.

A report from the raid on 17th December 1942 said that the first bombs started falling about 10pm. Warden post N1 reported at 12 minutes past 10 that the gas works on Monkgate had been badly damaged due to high explosives. Two gasholders caught fire. One fireman and an airman had been on duty and they were overcome by fumes and sent to hospital. The gas company had been prepared and had large quantities of puddled clay and long tools to deal with holes in gasholders. Just before 11pm an unexploded bomb was reported in the kitchen of 35 Bilton Street. There were various fires in the gardens of the Workhouse Hospital on Huntington Road. Behind this, on Amber St, a warehouse had been damaged. In The Groves, 120 incendiary bombs were dealt with by household fire guards except 1 where the National service was called. One or two of these bombs caused fires at Park Grove School.

The York Archives contain lots of photos of ARP wardens.

Air raid damage reports and maps are available from https://yorkairraids.wordpress.com/

The windows of shops and houses were taped to try to reduce the damage from flying glass during bombing raids.

How did people entertain themselves at this time?

The wireless played a large part in people’s lives. A regular show was ITMA, It’s That Man Again. The Home Service broadcast music, drama and comedy, news and public service announcements. One was a talk on ‘Making the Most of Tinned Food’.

Dancing to live music was very popular at this time. Residents flocked to the Albany Hall, De Grey Rooms, Clifton Ballroom, Terry’s and the Co-op Hall. People also had the choice of 10 cinemas and went on a regular basis.

To conserve fuel and free up trains for war use, cities put on events called Holidays At Home. From 9th to 23rd of August 1941 the programme of attractions included open-air dancing and concerts by bands like the West Yorks Regiment. Venues included Rowntree’s Park, the Museum Gardens, the Knavesmire and the Mansion House. August 1944 included talent spotting competitions, sheep dog demonstrations, donkey rides and Punch and Judy.

York children had lots of bomb sites to explore and look for shrapnel. On Foss Islands, where houses had been demolished, the Germans had dropped some stuff to interrupt communications. It was silver paper on one side, coloured on the other. Children made hulu-hulu skirts and danced around. Due to concerns that it might be contaminated, it was cleared away soon after.

Shelters

Public shelters included Marble Arch on Leeman Road, toilets in Parliament Street and St Sampson’s Square, the basements of Robson and Cooper, Hunt’s Brewery, the Woolpack and the Grand Clothing Hall on High Ousegate. Rowntree’s provided shelters in the orchard, rose lawn and in cellars.

Some public air raid shelters were put to good use after the war. The dogs’ home moved into the one at Castle Mills basin. The Park’s Department used ones in East Parade Glen Gardens and the Knavesmire Herdsman’s cottage. Pupils at Castlegate School used theirs as a sun shelter.

In addition to public air raid shelters, some residents built an Anderson shelter in their garden. Morrison shelters, consisting of a steel cage, were used indoors. They cost around a week’s salary but were free to people with an income of less than £250.Officials said that people had been saved by shelters. Morrison shelters had been found to be remarkably safe.

The Public Library

Women took over the running of York library during the war. Duties included ordering the books. Due to the number of overseas service men in the area the library brought a stock of American books. Members of the public could only take 3 books out at a time then.

My great aunt, Kath Dawson (nee Woods, born York 1920), was private secretary to the manager and worked in the children’s library. She helped to put on entertainment for American officers stationed nearby. She took part in a large war time fund-raising parade. She was allowed to wear a white/purple striped dress from the Castle Museum.

My mum’s cousin Joan Maybury (nee Guest, born 45 Bilton St, 1934) remembers her grandad Harry Woods going fire watching. She tried his helmet on. It was so heavy that it split her bottom lip when it slipped. Men who worked for York Corporation or the County Council became very busy when the many airfields around York were being built. Airfields were built on land which had previous been farmed. Joan said that Harry Woods was given farm-made cheese and rabbits by farmers when he was working for the Corporation on airfield building.

Joan said that an air raid was targeting the gas and electricity works but they remained unscathed, but a street in Layerthorpe was bombed and a house completely disappeared. Granny Woods’ house had the glass blown out. Grandad Woods as ARP warden helped batten everything down. Joan had a budgie called Joey. She waked to the library with the budgie. Kath had been fire watching at the Minster. Nothing had hit the Minster. Kath had a camp bed in the children’s library. Joan was placed on the bed with warm blanket and a pillow and given sweetened cocoa as a treat and was given her favourite books. The next morning, they walked through town and Joan said it was like walking through rubies. The sky was bright red. Joan found it exciting. She said that in one of the bombs meant for the Minster some brave person had substituted a note for a fuse. She said the bomb and note was given to the Castle Museum.

Are we left with anything from that time?

The most obvious is St Martin-Le Grand down Coney Street. Left almost wholly destroyed by the Baedeker raid the site is now a Shrine of Remembrance to people who died during the war.

Rowntree’s were using their original factory, at Tanner’s Moat, for storage up to 1942, but the Baedeker raid caused too much damage for this to continue. Following demolition this area was gifted to the City by Rowntree’s. The subsequent garden was paid for by the Joseph Rowntree Village Trust, which we now know as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Some pre-war houses in York still have bullets holes in their outside walls following dog fights. Some cracks in plaster and fragile ceilings are the result of the explosion of a gasometer.

Wartime always hastens development of things. These include blood transfusions and blood banks; antibiotics and childhood jabs. Night vision photography was tested by the RAF during the Second World War.

The end

A Civil Defence report summing up the War said that 87 people had been killed and 111 seriously injured. 9,500 homes (34% of the total) had been destroyed or damaged. Air raid sirens had sounded 138 times. 2,554 people had enrolled in Civil Defence by April 1942. This number was in addition to the Police, National Fire Service and Welfare Services.

The official victory celebrations for York took place on 8th June 1946.

Leave a Reply